Sexism is alive and well

© Rachel Whiteread

© Rachel WhitereadCara Phillips brings our attention today to the disturbing point of view of the ever-controversial British art critic Brian Sewell on her blog, see here. She cites Sewell and his sadly discriminatory remarks toward women as a means of explaining why she and Amy Elkins started Women in Photography. An article in the Independent yesterday quotes Sewell as saying: "The art market is not sexist...The likes of Bridget Riley and Louise Bourgeois are of the second and third rank. There has never been a first-rank woman artist. Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness."

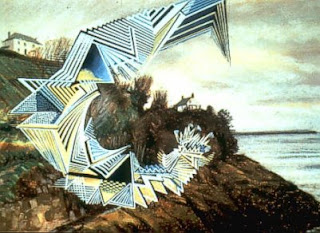

In a separate article published in 2005 in The Guardian he stated: "Women are no good at squeezing cars through spaces. If you have someone who is unable to relate space to volume, they won't make a good artist. Look at Barbara Hepworth--a one-trick pony. Look at that pile of rubbish in the Tate by Rachel Whiteread."

Sheesh...

The temptation is to get into a lengthy discussion about the multitude of first-rank female artists who are out there, past and present, and to begin a debate on the small-mindedness of implying that one of the reasons that only men are capable of aesthetic greatness is because, in Sewell's opinion, women can't drive. But his view is so full of his own term "rubbish" that I don't believe it even merits a full discourse.

What I will do is move on to another quote in the Independent article in which the author writes: "Pilar Ordovas, the head of contemporary art at Christie's, also rejected claims the market is sexist. 'There are many male artists who sell for the same as women...It is too simplistic to suggest that gender or age determines price.'" But is it?

In his book Blink, Malcolm Gladwell writes extensively on gender bias in relation to hiring practices among orchestras. On Slate he summarizes:

"Prior to the 1980s, auditions for top orchestras were open—that is, the auditioning committee sat and watched one musician after another come in and play in front of the judges. Under this system, the overwhelming number of musicians hired by top orchestras were men—but no one thought much of this. It was simply assumed that men were better musicians. After all, what could be fairer than an open audition? And weren't the members of audition committees, "experts" in their field, capable of discerning good musicians from bad musicians?So here we have concrete evidence of gender bias in a creative field. This is not to say that those who did the hiring were overtly sexist or even aware of the preference, but the preference existed nonetheless. On a basic level gender bias is deeply pervasive in Western culture, and I believe it's so ingrained that even those of us who consider ourselves enlightened can fall prey. I remember instances in my (luckily) more distant past when I would be reading an article in a newspaper or journal, would think it was brilliant, and then on discovering the author was a woman feel my esteem go down a notch. I was always taken aback by this shift in my perspective, and it was only in challenging myself and even actively seeking out powerful artistic female role models that I now no longer have such a change of heart based on gender. Still--if I as a creative woman could fall prey to such bias against my own sex, what about those who never question their assumptions? Or those who wholeheartedly embrace their misogynistic attitudes?

But then, for a number of reasons, orchestras in the 1980s started putting up screens in audition rooms, so that the committee could no longer see the person auditioning. And immediately—immediately!—orchestras started hiring women left and right. In fact, since the advent of screens, women have won the majority of auditions for top orchestras, meaning that now, if anything, the auditioning process supports the conclusion that women are better classical musicians than men. Clearly what was happening before was that, in ways no one quite realized, the act of seeing a given musician play was impairing the listener's ability to actually hear what a musician was playing. People's feelings about women, as a group, were interfering with their ability to evaluate music."

It makes me wonder: what if Brian Sewell had to judge a large group of individual works of art, receiving no information about the artist's gender--would he still conclude the female artists to be second and third-rank? As far as Christie's and the work of men selling for so much more than women, unfortunately there's no way for auction houses to put up screens, as it were, because the pieces are being sold for so much money largely due to the clout and reputation of the artists who created the work. But it does get one to thinking about the various shows and rounds of jurying that occur on a continual basis--would anything change if no name were included with submissions by emerging artists? Don't get me wrong, I think things are improving--at least where I've been paying attention, which is within the photography world--and as more female innovators like Jen Bekman rise to the top I can only hope that the playing field will level out--that the best, regardless of gender, will receive the accolades they deserve.

Comments